Everything you need to know about Ethel Smyth’s ‘Der Wald’

Smyth’s second opera now has its WORLD PREMIERE RECORDING

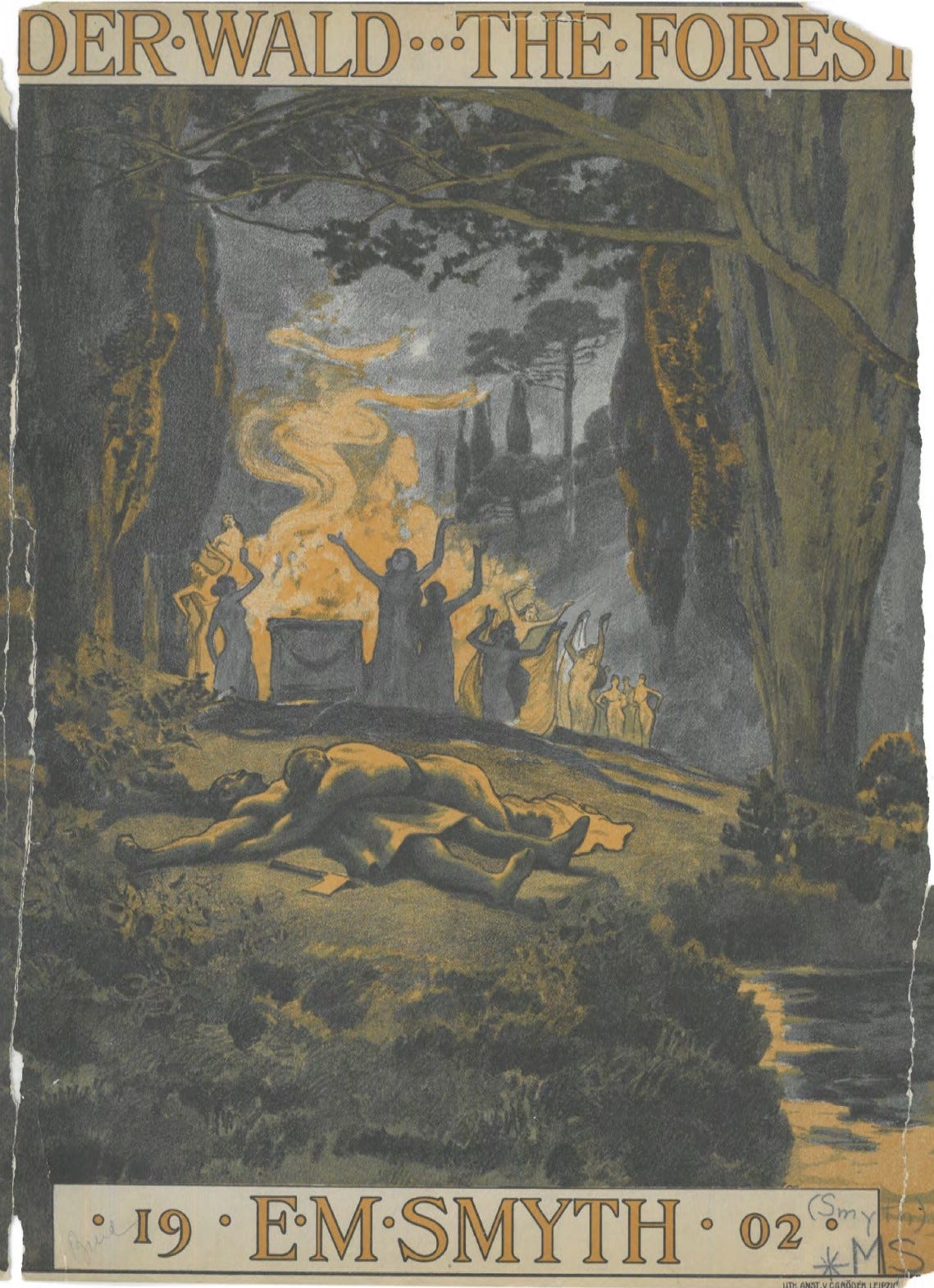

I may have mentioned this one or a hundred times, but Ethel Smyth’s second opera Der Wald has just got its world premiere recording. Not only is this exciting if you’re interested in Smyth, but it’s exciting if you’re interested in classical music generally. Der Wald (‘The Forest’) was a historically significant work, and this recording allows us to hear it for the first time. It was the first opera by a woman staged at both the Metropolitan Opera in New York and Covent Garden in London. Smyth was composing at a time when Brits were trying to form their own operatic culture, so as one of the few British operas heard in the UK during this period, Der Wald was understood as an important step towards “British” opera. So as you dive into the recording, this is everything you need to know about Der Wald.

Der Wald took years of planning

Der Wald wasn’t premiered until 1902, but Smyth first started thinking about this opera in 1896. She planned it out with her lover and artistic partner, the writer Henry Brewster. They had a long and complex relationship history (which I’ve written about in Quartet), but by 1896 they were firmly committed to one another. Brewster was Smyth’s confidante, muse, and creative collaborator. Pleasingly for posterity, they lived in different countries, so much of their creative work was carried out on paper, giving us an intimate insight into how they worked.

One of the things that attracted Smyth to Brewster was how well-read he was. She adored people who challenged her intellectually, and they debated their favourite books in great (and sometimes heated) depth. His first suggestion was for her to craft a libretto that adapted a Thomas Hardy novel, perhaps Tess of the D’Urbervilles. Smyth rejected this option, but frustratingly her reply hasn’t survived to tell us why. Perhaps there simply wasn’t enough dramatic action, or the character of Tess didn’t provide the right material for the powerful female characters that she loved to write.

Instead, she countered with a proposed historical opera. Smyth adored Shakespeare, and possibly she was drawn to this idea as a kind of musical answer to his history plays. Brewster, however, was unenthused by her libretto. She sent him a plot full of twists, turns, political intrigues and secret love affairs. ’You must not think me nasty’, he wrote, ‘but ought a musical drama to be like a Bismarck puzzle?’ He felt that Smyth’s scenario was just too complicated to work on stage. ‘Don’t hate me, dearest’, he begged. ‘I think of the quality of the music you would write and therefore want the words to be worthy.’ He offered another suggestion:

What I like is this: a scene in a forest; a pair of simple lovers, a lustful queen out hunting, and a catastrophe. The whole thing in one act reduced to elemental themes: the peace and freshness of the forest, innocent joyful love, lust, jealousy, despair, death; the sound of the huntsman’s horn and the silence of the forest closing over it all again.

Smyth loved it. Simple, clear, dramatic — this was the idea that would become Der Wald.

Critics were shocked by the ‘modernity’ of the score

Smyth was never one to underplay her own talents. Yet her verdict on Der Wald was simply that she had ‘a weakness’ for the score. It was her third opera, The Wreckers, that she thought of as ‘the work by which I stand and fall’.

It is, in some senses, unsurprising that Smyth favoured The Wreckers. She was desperate to be taken seriously as an opera composer, and Wreckers is both larger and longer than Der Wald. In one act with a running time of just over an hour, Der Wald is much more compact. I can see why Smyth wanted to promote The Wreckers first and foremost, proving that she was just as capable of working on a large canvas as her male counterparts. In addition, Smyth had a particular emotional attachment to The Wreckers, because it was both her most intense and her final collaboration with Brewster. While he was involved in the inception of Der Wald, it was Smyth who ultimately wrote the libretto. They reversed roles for The Wreckers. Smyth came up with the idea and Brewster wrote the text — and he died shortly after its first London performance.

Finally, The Wreckers was slightly more popular than Der Wald in Smyth’s lifetime. Because she detached the Overture and Prelude to Act II as stand-alone orchestral pieces, these two excerpts from The Wreckers could be performed by orchestras. The Prologue for Der Wald involves a chorus, making it less adaptable for orchestral performance. She did eventually rework moments from Der Wald in to choral pieces, but they didn’t have the same independent lease of life as the Wreckers Overture and Prelude. So when Smyth wrote her books to promote her music, it was The Wreckers that she focused on.

Comparing the operas now, however, things look a little different. Although they are completely different beasts in many ways, Der Wald is just as well-wrought and compelling as its successor — perhaps even more so. Dramatically, their main similarity is that they both have plots driven by a love triangle in which a man is fought over by two women. As I’ve written about here, Smyth often composed autobiographically. I doubt it’s a coincidence that these operas centre on this scenario when she herself had been embroiled in a love triangle for many years with Brewster and his wife, Julia. In Der Wald, Röschen and Heinrich are in love and set to be married — but are pulled apart by the witch Iolanthe, who desires Heinrich for herself. When he rejects Iolanthe she kills him, and Röschen dies of a broken heart.

When critics first heard Der Wald they were shocked by the score, saying that the opera belonged to ‘the most modern school’. We have to remember that when this opera premiered, Strauss’s Salome had not yet been written and Debussy’s Pélleas et Mélisande had only just been performed. Der Wald predates Schoenberg’s searing one-act monodrama Erwartung (1909, and not premiered until 1924) and Zemlinsky’s psychologically intense one-acters Eine florentinische Tragödie (1915-16, prem. 1917) and Der Zwerg (1919 prem. 1922). Both musically and dramatically, Smyth was at the forefront of opera developments in the early twentieth century.

Partly, Smyth manages to achieve such a convincing dramatic tension in the score by synthesising a combination of musical styles. In the music of the forest that bookends the opera, she uses what conductor John Andrews describes as ‘a fairly conservative, late 19th-century, rich, sensuous Romantic idiom — depicting the forest and the people living and working there’. Key influences are Mendelssohn, Verdi and Brahms. In the Prologue, her harmonies nod to Mendelssohn’s music for A Midsummer Night’s Dream, while her choral writing and orchestration sit closer to Brahms’s Requiem and the choruses of Verdi’s early operas like Nabucco.

The mood changes, though, in the second scene. Smyth gives us a lively dance complete with an incredibly catchy main theme, but interrupts it with an offstage horn call — a call that announces the presence of the witch Iolanthe. This is where we start to enter into the psychological core of the opera, and Smyth’s writing shifts accordingly. From the moment Iolanthe comes on the scene, dissonance increases, the music’s key becomes more uncertain, and lower registers dominate the orchestration. The bass clarinet growls out through the orchestra, and will become associated with Iolanthe specifically. From here, the music becomes, in Andrews’s words, ‘almost expressionist’ as she constructs ‘the dark, supernatural forces that bring chaos and destruction.’

The effect is like hearing through a musical telescope — we begin with a wide view of the forest, zoom in to witness the intense drama between Iolanthe, Röschen, and Heinrich, and then zoom out again after their deaths. In the central section, the tension does not let up for a second. Smyth gives us music of overwhelming passion in the duet between Röschen and Heinrich that presages Marc and Thurza’s love music in The Wreckers, while Iolanthe’s part is nothing less than a feat of endurance. The most experimental music is reserved for the scenes in which Iolanthe is present. And although she is technically written as a mezzo-soprano, Smyth repeatedly pushes at the extremes of the mezzo range. Iolanthe is a powerful, physical role.

The premiere was a disaster

No matter how compelling a composer’s music was, they were always slightly at the mercy of events beyond their control. In Smyth’s case, she had the misfortune of being a British composer premiering an opera in Germany during the Second Boer War. British action in South Africa had been hugely unpopular in Germany, to the point where Smyth reported that the conductor only agreed to lead Der Wald on the condition that he would not have to be friendly with the composer, because ‘of the atrocities committed by the English in the Boer War’.

In this political climate, when Der Wald opened at the Berlin Court Opera, both critics and audience expressed their dissatisfaction with an English composer’s work being prioritised over a German. At the first performance, ‘organized booing and cat-calls broke out in three different parts of the house’. The reviewers unanimously dismissed the opera. Her gender was always a barrier for critical appraisal, but the tone was at least usually courteous. With the excuse of an unfavourable political situation as a backdrop, the reviews became an outlet for undisguised sexism. Smyth was a ‘composing Amazon’ who had produced ‘the well-meaning work of a dilettante…who has not learnt nearly enough to conceal her lack of invention with even a degree of skill’. Another was not so generous, lambasting it as ‘really incredibly childish, and even below the level of dilettantism.’ In sum, ‘the work of the English composeress did nothing to weaken the prejudice that one is generally accustomed to show for female compositional activity.’

Smyth was, understandably, extremely upset. She wrote frustratedly to Brewster, who tried to console her by saying that ‘I firmly believe that it is an exceptional and beautiful work’. He was also practical though, and encouraged not to lose heart and to persevere no matter what. ‘If the public is not ready for the work nothing will make it succeed at the present moment’, he continued. ‘It is possible, though I hope otherwise, that the shortest way to the forest may be through some other work’.

Der Wald was the first time that Smyth expressed a “feminist” attitude

More retiring personalities than Smyth might have been completely defeated by this kind of critical reception. But Smyth did what she did best. She fought. ‘I feel I must fight for Der Wald’, she said, because ‘I want women to turn their minds to big and difficult jobs; not just to go on hugging the shore, afraid to put out to sea.’ This was the first time that Smyth expressed the desire to embrace gender-based solidarity, and to be a leader for other women. She had spent most of her youth trying to be accepted as an honorary man, and had often distanced herself from other composing women in an attempt to avoid the pejorative “woman composer” label. By the time that Der Wald premiered, though, it had become quite obvious to Smyth that however she wanted to be perceived, other people would continue to see her as a woman first and an artist second. The critical reception was a tipping point, pushing Smyth towards a less isolated stance.

I suspect that a woman called Lady Mary Ponsonby was also behind Smyth’s changing attitudes. It was quite usual for Smyth to be romantically involved with multiple individuals at the same time, and one of her primary romantic partners while she was with Brewster was Lady Ponsonby. She was, by any accounts, a truly formidable woman. Granddaughter of a Prime Minister, she had been a lady-in-waiting to Queen Victoria, and when Smyth met her was wife to the Queen’s Private Secretary. She shot, smoked, played pool, painted, read voraciously, and had a carpentry workshop in her garden. Smyth was besotted. She was attracted to everything about Ponsonby — her intellect, her voice (which she said gave her a ‘strange, half physical pleasure’), and most especially a veneer of self-restraint that concealed passion and a fierce determination:

In no human being I have ever met were hidden such inexhaustible stores of fire as in the heart of this apparently calm, deliberately reserved, rather sphinx-like being, who possessed among other peculiarities the art of settling down with her book or newspaper in her armchair, or in a railway carriage — quiet as the hills and as though established there for all eternity.

Importantly for Smyth’s story, Ponsonby was a committed advocate of women’s rights. She held unusually liberal political views for a woman of her class, and believed strongly in the importance of women’s education and employment. She sat on the committee involved in the founding of the first Cambridge college for women, Girton College, and lent her time and name to a number of women’s rights groups. Ponsonby’s influence seems to be written all over Smyth’s decision to respond to the Der Wald debacle in the manner that she did, putting her on the path that would culminate in her being imprisoned in Holloway for her involvement in the militant suffrage campaign.

The opera was staged in England and the United States

Smyth’s determination paid off. She was offered contracts for productions of Der Wald at both Covent Garden in London and the Metropolitan Opera in New York, making her the first woman to have an opera staged at each venue.

The producer for the Covent Garden performance was Francis Neilson, who thought Der Wald ‘a strange and beautiful thing’. He left behind a memorable image of a tam-‘o-shanter clad Smyth being a one-man-band, playing and singing through her operas to others:

She played it, while smoking cigarettes incessantly. She would even stop in the middle of a scene to light another and, when…offered…a cigar, she took it and said that she would smoke it after dinner, that it was a pity to ruin a good cigar by letting it go out every now and then.

He worked closely with Smyth on the production, and she remembered it as ‘one of my few almost wholly delightful operatic experiences. I had a splendid cast, and a first-rate stage-manager and producer rolled into one’. She was so pleased to have an opera staged at Covent Garden that she even ditched her usual tweeds for ‘a modest evening gown of pale heliotrope silk’ for the first performance. This was sufficiently out of character that when the curtain fell, ‘Lady Ponsonby, sitting in a box not far from the stage, was heard to exclaim, “Who is the little woman with Neilson?” A friend told her it was Ethel. “I can’t believe it,” her ladyship replied. “Ethel never looked like that.”’

Compared to Berlin, the London reviews were extremely favourable. Considerations of nationality tempered criticism in both countries — where Smyth’s Britishness had played against her in Germany, in England The Globe praised Smyth for having ‘given us the thing that we have wanted so long — really fine opera by a native composer.’ They thought her music ‘fresh and spontaneous’, especially praising the second scene's dance. The Pall Mall Gazette hailed it as ‘a distinct and unique triumph’. The reviewer declared themselves ‘deeply, very profoundly, touched by the exquisite workmanship of the score’, thinking the composition ‘superlatively original’, demonstrating ‘absolute modernity’, and rising ‘at times to moments of absolute genius.’ If one left feeling that Der Wald ‘is not a masterpiece’, they declared, ‘the ear has been deceived possibly only by reason of the music’s extreme modernity.’

So it continued. Nonetheless, appraisals were still tempered by consideration of Smyth’s gender. The Daily Telegraph declared it ‘keenly interesting’, but caveated this with the comment that ‘nothing that a woman’s pen has given to the art of music [is] so intellectually worthy as the score of Der Wald’ (my emphasis). The Referee wrote that ‘few examples of serious dramatic works by ladies exist, and of these Miss Smyth’s is far and away the strongest.’

When Der Wald went to the United States, gender was foregrounded even more noticeably. Smyth had whipped up a considerable amount of publicity ahead of her New York appearance, and journalists were keen to meet the ‘English Girl’ who was causing such a stir by writing operas. She was considered first and foremost a novelty — ‘the peculiarity of a woman’s name attached to an operatic composition is attracting wide curiosity’, the Savannah Morning News reported, ‘and the approaching performance is being looked forward to with interest.’ Writers focused on her as a personality, and an interview she gave for the New York Daily Tribune further emphasised her gender. ‘The life of any composer…and especially that of a woman musician, is one long battle from start to finish’, she said. ‘I feel that I have a duty to all womankind in persevering in this field. Every woman that comes after me will find it easier because of my journey first over the rough road.’

This was a level of hype that would be difficult to live up to — and all of it centred on Smyth being a woman. When the New York reviews came out, they trotted out many familiar clichés about music written by women. The opera demonstrated ‘vaulting ambition and a general incompetency to write anything but the most obvious commonplaces’ (New York Times); it was the result of ‘considerable skill, rather than of a deeply felt and irresistible musical inspiration’ (New York Times again); she had ‘acquired pretty skill in orchestration’ but not ‘melodic sense’ (New York Daily Tribune). The reviewer for The Sun decreed that the opera failed because it was dealt with the difference between love and lust, and ‘woman with all her intuition cannot penetrate this corner of human experience. It is just the one thing in life that she can never know, unless she ceases to be a woman.’ (!!!!!!!) The writer continued that ‘always in this opera one feels the presence of a strong, ambitious, dominating mind, but one does not feel the mastering influence of a tumultuous throbbing temperament’. Freud would have a field day.

It would be comic, were it not for the fact that these were the people who determined the direction of not only Smyth’s career, but the careers of all women composers trying to make their way in the early twentieth century. Smyth scholar Amy Zigler has surveyed the US reception of Der Wald, and concluded that ‘critics beyond New York City and the surrounding metropolitan area applauded her success…and by all accounts, audiences loved it. Unfortunately for Smyth, the New York critics’ opinions were the ones that mattered’. And the New York attitude could be summed up by the following from the Evening World:

After an hour of ultra-modern music, strident, formless, passionate music that stirred the blood with clangor of brass, the shrieks of strings, the plaint of woodwinds and disdained to woo the senses with flower soft melodic phrase, the audience at the Metropolitan Opera House clamoured for the composer and held its breath when she appeared. A fragile creature, feminine to her fingertips in rather old-fashioned gown of black silk, red roses in her dark hair and a curtsey like grandmother used to make, beamed her happiness, while the house rang with cheers and plaudits and the stage filled with flowers. … Of course the personal element predominates in American criticism and last night’s audience thought first of the incongruity between the dainty little woman and the rugged masculine music her fancy had evoked. Her work is utterly unfeminine. It lacks sweetness and grace of phrase. Wagner was never so ruthless in his treatment of the human voice.

Smyth had hoped that her opera would help to make life easier for other women composers. Sadly, it might have had the opposite effect. The negative, gendered reception of Der Wald could be used as evidence to shore up the preexisting belief that women could not compose opera. It took over a century for the Met to stage another work by a woman — Kaija Saariaho’s L’Amour de Loin in 2016.

The history of Der Wald is bittersweet. On the one hand, it was a major breakthrough for Smyth. One the other, the circumstances surrounding the opera’s first productions are a sad indictment of the world in which she lived. It shouldn’t have been remarkable for a woman to have her work staged at these venues. It shouldn’t have been acceptable to write about that work in such gendered terms. And it certainly shouldn’t have been possible for Der Wald to be the only opera by a woman that the Met staged in the twentieth century. I hope that this recording will give Der Wald the life it should have had in 1902, allowing Smyth’s opera to be brought back to stages once more.

All quotes from Henry Brewster’s letters appear courtesy of the San Francesco di Paola/Brewster-Peploe Archive, Florence.

Der Wald is out now on Resonus Classics. John Andrews conducts the BBC Symphony Orchestra and BBC Singers, with soloists Natalya Romaniw, Claire Barnett-Jones, Robert Murray, Andrew Shore, Morgan Pearse and Matthew Brook.

If you want to find out more about Ethel Smyth and Der Wald, I’ve written about the importance of recording historical works for VAN Magazine here. Conductor John Andrews is interviewed about the music on Opera Today here. Amy Zigler’s article is available in the December 2021 edition of Opera Journal, for those who have a subscription.

An new production of Der Wald is upcoming at Wuppertal Opera House in April 2024

I’ve just started reading your Quartet book this weekend, I love reading about unsung composers! I’ll have to have a listen to Der Wald this weekend. Great to hear the BBC Singers as well after this year’s controversies.