Ruth Gipps in her own words

How Ruth Gipps became an outsider

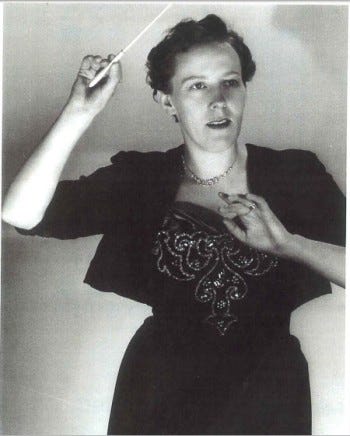

Those who knew the composer Ruth Gipps often describe her as a “difficult” personality. She saw herself as an “outsider”, and she wore that badge with pride. Unafraid to cause offence, she penned scathing poems poking fun at musicologists and was outspoken about her religious beliefs. She gained a certain amount of notoriety by writing a public ‘Credo’ denouncing modernism and pop music when modernism and pop music were very much in favour. At a time when Vaughan Williams was distinctly unfashionable, she proudly declared that her music was ‘a follow-on from Vaughan Williams, Bliss and Walton’. She considered them all ‘great and inspired composers’ — and that ‘so-called 12 tone music, so-called serial music, so-called electronic music and so-called avant-garde music’ was ‘utter rubbish and indeed a deliberate conning of the public.’

Being “difficult”, though, characterises a lot of historical professional women — they had to be abrupt and belligerent to make any headway at all. In her unpublished autobiography, Gipps wrote candidly about her journey to becoming a “difficult woman” who was unafraid to stand up for herself and her beliefs. Whether autobiographies are entirely factually accurate or not, they tell us so much about how the author wants other people to perceive them. And for Gipps, a significant portion of her writing is dedicated to establishing herself as an extraordinary woman, who had to fight prejudice and discrimination to become the person she was.

Growing up

Gipps was a child prodigy — a concert pianist who won her first composition competition at the age of eight. By her account, at least, she was never pushed by her parents. Her mother was a piano teacher and introduced her to the instrument, but Gipps flourished at performance because simply adored playing the piano. ‘Really’, she thought, ‘I found it incomprehensible that anybody shouldn’t enjoy every minute of playing.’

Being a concerto soloist who could barely reach the pedals, however, attracted an unusual amount of attention, both good and bad. She received multiple concert engagements and ‘was loaded up with toys, flowers and chocolates’ when she performed — but she also remembered being regarded ‘with sympathy and horror’ as ‘an unnatural child, revoltingly precocious’. From a very early age, Gipps knew that she was seen as unusual, which was only reinforced by her experiences at school. ‘I seemed to myself ordinary in the extreme’, she recalled, but ‘whatever the reason, I was a born bully-ee.’

Of all the trials Gipps encountered in her life, the ones she recounted with most horror came from her school days. School, it seems, was far from a happy time. Whether it was being struck down with glandular fever from overwork or being banned from musical practice that distracted from her schoolwork, Gipps narrates her school life as a litany of woes. And perhaps most importantly, it was her time at school that instilled in her that she wanted to be “one of the boys”. ‘At seven I learnt that I, who was always odd one out with girls, got on fine with boys; they very, very nearly accepted me as one of themselves.’ As Gipps saw it, the gossipy bullying she endured from other girls was intolerable, but she could see the boys off by showing them she was not afraid of them. She tells the story of a formative encounter when she was eight:

…a big boy barred my way. I believe he was called Philip, and he was ten. I was somewhere near my eighth birthday, and puny at that. Desperately I put up my useless, untrained fists, and said “Leave me alone! I can fight, you know!” Philip deposited me swiftly but painlessly on my back on the stone floor and waited for feminine tears of fright. They didn’t come…I got up in silence, scared but game, and put my fists up again. From that moment the boys were my friends. I had passed their test; I hadn’t cried, and none of them ever again lifted a finger against me…there is no real difference between men and women, but personally I prefer men.

This set up a pattern of behaviour that Gipps replicated all her life. She tackled adversity with blunt force — whether it was the most effective solution or not. And although as a conductor she did sometimes support other women composers by performing their work (for Florence Price’s centenary, for example, she gave a concert including Price’s Piano Concerto — which I think might have been the UK premiere?), as a general rule she distanced herself from other musical women. And working in a field so hostile to women, this only meant that she would find herself increasingly isolated. Other composers like Rebecca Clarke found networks of supportive women to help navigate their way through the intensely patriarchal world of classical music together. Gipps, however, would have to make her way on her own.

Becoming Ruth Gipps

Writing a memoir seems to have been a way for Gipps to think through some of her unease about her identity, and the expectations placed upon her because of her gender. At a relatively young age, ‘the notion of my own femininity had not dawned on me; I was at ease in boy’s clothes, and kept my troublesome hair as short as possible.’ As she grew older, however, it became clear that ‘Ruth Gipps, the girl on the poster who played at concerts, must be prettily dressed for the platform; this I accepted, but the real me, the girl at home, scorned anything so feminine as interest in clothes. So long as the colours were bright, for so long as the shorts were boys’ shorts, their elegance or otherwise didn’t concern me.’ She divided herself into public and private personas — Ruth Gipps the conductor and composer, and ‘the real me’ who was called Widdy, or Wid for short, and felt much more like a boy than a girl.

Given that she took such care to present a beautiful, feminine stage persona as this was expected of women, she found it doubly frustrating when this was then criticised by her colleagues as ‘self-advertisement.’ It felt as though she couldn’t win. Rather than buckling under pressure and wearing less eye-catching clothing, however, Gipps stuck to her guns and continued to don brightly coloured clothes, having inherited from her mother ‘a hatred for grey, beige, oatmeal, brown or navy-blue clothes.’ As Gipps’ biographer Jill Halstead has observed, ‘she seems to have actively constructed a more feminine self, a sexual self’ for the stage, miles away from her day-to-day existence where she favoured ‘a more androgynous appearance.’

Having been made acutely aware of her gender as a child, later reinforced by working in a profession which marginalised women, Gipps’ views about gender were both strongly held and contradictory. On the one hand she complained about ‘men with minds out of the Ark who thought women shouldn’t play Brahms’, while on the other she claimed that the ‘business about men players not liking women conductors is a bogey invented by women who were too afraid to take a chance.’ Alienating herself from both men and women, Gipps felt most at home among animals, whom she considered her ‘passion’. And yet her students and those who played in her London Repertoire Orchestra remember her warmly — she genuinely wanted to help younger musicians succeed, and they maintain that she had a kindness behind her prickly exterior.

Gipps worked in the two areas of music considered most beyond women’s reach: conducting and composing. Like all women of her generation who harboured ambitions in these careers, she found twentieth century attitudes to be relentlessly inhospitable. After hearing Gipps conduct Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony at the Royal Festival Hall, one critic blustered that ‘a woman is no more expected to conduct it than build a Great Boulder Dam’, expressing astonishment that she had the audacity to even approach ‘one of the Everests of music.’ Living in this world, she couldn’t help but be an “outsider”. Time and again she learned that if she wanted a musical career, ‘my only hope was to have behaved as I did’. So she chose to embrace her outsider status and make it a part of her professional persona, seeing it as the only way that a woman could even hope to be an insider in classical music.

If you want to find out more about Ruth Gipps, I’ve recorded a documentary about Vaughan Williams’ students which features Gipps here: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m001cnt3

You can also hear her Second, Third, and Fourth Symphonies in recordings by Rumon Gamba and the BBC Philharmonic and the BBC National Orchestra of Wales.

Do you know where we might find this memoir?

I would love to be able to use this photo of Ruth to promote the orchestra I work for! We are performing one of her pieces this year and I can't seem to find a way to source images of her. Would you mind sharing where that image of Ruth can be found for licensing?