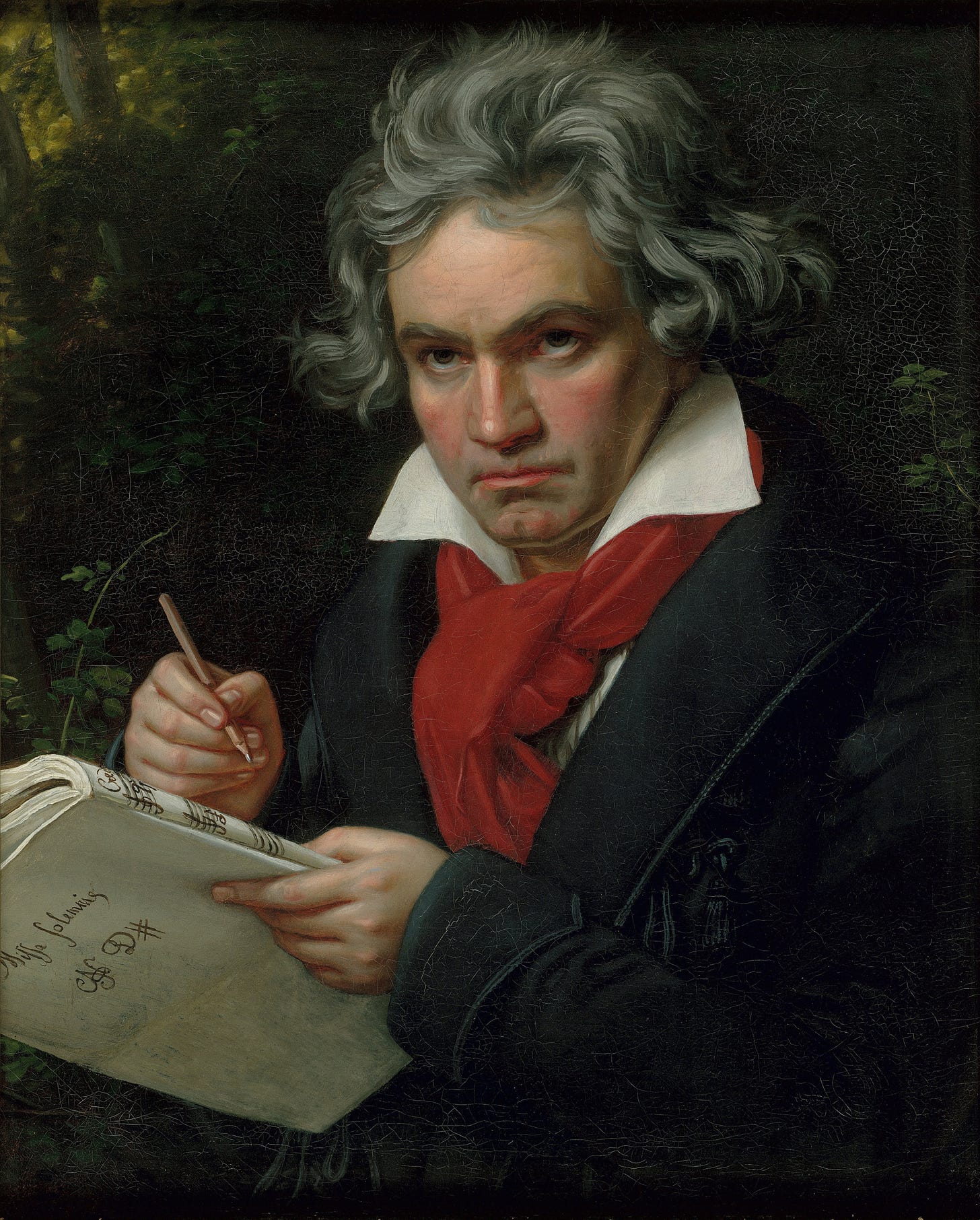

When women composers are compared to the “greats”, it doesn’t usually end well for the woman. This is especially true when they’re being compared to Beethoven, so often held up as a compositional gold standard, the greatest of the greats.

In her lifetime, Ethel Smyth had to put up with a lot of Beethoven comparisons. When her Mass premiered in 1893, it was described by The Weekly Dispatch as ‘exemplifying that ambition which overlaps itself’ — that she had tried and failed ‘to emulate Beethoven and other masters whose utterances are couched in the loftiest spirit.’ Reviewers used Beethoven to inform readers that women had only shown themselves capable of imitation, not creative genius. Women had written ‘clever’ music, but ‘the world is still waiting for one who shall be called great’, who could ‘do among women what Beethoven did among men’, the Daily Telegraph lamented.

Fifty-one years later, in Smyth’s obituary, the same newspaper rolled Beethoven out to criticise Smyth’s involvement in the suffrage movement. ‘Fancy Beethoven taking two years off because some energumen of his acquaintance wanted his assistance in an agitation for the extension of the Parliamentary franchise!’, the critic spluttered. ‘It is lucky for us that those great composers were not so frivolous.’ (One wonders what the politically-minded and famously confrontational Beethoven would have done if faced with consistent gender discrimination that made it much harder for him to work.)

The long history of using Beethoven to diminish women makes me extremely cautious of using him as a comparison point. Nonetheless, watching the BBC’s coverage of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony at the Proms this weekend, I couldn’t help but think of Ethel Smyth. The pre-Prom show was a re-run of an episode from a documentary called Being Beethoven. The focus for much of the programme was on how Beethoven coped with hearing loss. Musicians and biographers pored over the Heiligenstadt Testament, explaining why it was such a significant document for the composer, who chose to continue writing and working and living even after realising that he would go deaf. ‘Beethoven had about as much courage as a human being can have’, we are told. Then came the discussion panel just before the concert. Beethoven was described as a rebel, iconoclast, innovator — musical details were picked out to explain how the piece is put together, and why it was thought of as groundbreaking at the time. There was much discussion of Schiller’s ‘Ode to Joy’ words, and how the text’s philosophical content is a large part of the symphony’s enduring importance.

The parallels between Beethoven and Smyth here are so striking that they are impossible to ignore, and yet I have never heard Smyth described in evenly remotely comparable terms. Smyth also experienced severe hearing loss in middle age, and wrote movingly about its impact both on her work and on her personal life. Her hearing loss manifested in her being plagued by noises, from booming to flapping and whistling. ‘I struggle in vain against the growing depression caused by this trouble’, she confessed to her diary in 1919. ‘On free days I am full of hope & enjoy life’, but now ‘I see nothing in life but..enduring unto the end with as little distress to friends etc as may be.’ In the same way that the Heiligenstadt Testament gives an insight into the way that deafness impacted on Beethoven’s outlook and creativity, Smyth’s letters and diaries tell us something about how she coped with her deafness. ‘Life has got to be faced somehow, now that I see that nerve-wracking conditions of existence & eventual deafness are my lot. I’ve put all my affairs in order & devoutly hope another attack like the one of last Oct may put an end to it all.’

Beethoven and Smyth’s experiences were extremely different, but if Beethoven’s attitude was ‘courageous', then so, too, was Smyth’s — especially when we consider that when she composed her final works she was additionally suffering with lumbago, arthritis, and a number of other ailments that made it difficult to even hold a pen without pain. Despite being unable to hear clearly or write easily, like Beethoven Smyth continued to compose, albeit it with difficulty. When her hearing loss was at its most acute, she wrote her operas Fête Galante and Entente Cordiale, her Concerto for Violin, Horn and Orchestra, and her final large-scale work, a symphonic cantata called The Prison. Like Beethoven’s Ninth, The Prison is a philosophical work. Set to a text by Smyth’s lover Henry Brewster, who died from cancer in 1908, it reflects on how we cope with death and ideas of immortality. Is this not a topic of as widespread significance as the ideas about universal brotherhood dealt with in Schiller’s ‘Ode to Joy’? Smyth composed The Prison in agony, when she ‘could only play the piano as a fly crawls over a window pane — & often as I did so wept from pain.’ Is that not a feat of endurance and defiance in the same way as Beethoven’s last symphony?

We might want to question upholding Beethoven as an icon and hero, and the whole ideology of “great” composers. But Beethoven’s story touches on so many fascinating questions that interest in him is unlikely to disappear any time soon. How people overcome adversity, how art is created even under the most unlikely circumstances, how music can express or escape from human suffering, how artists have dared to imagine a better world: Beethoven’s biography speaks to all of these. And so does Ethel Smyth’s. Watching the Proms coverage, I wondered how it would change Ethel Smyth’s position today if she was talked about with the kind of language and framing that Beethoven is given — if we asked the same questions of her life and music that we ask of Beethoven’s. They were such different people that her life and music would give us quite different models for personal perseverance and artistic expression. But also fascinating might be the similarities between these two individuals separated by time, place, nationality and gender. What might we discover by giving Smyth the same care, attention, and even reverence that is so frequently afforded to Beethoven?

By this point I have done a lot of events talking about Smyth, and I’m struck by the regularity with which I’m asked to tell funny anecdotes about her. The story about her conducting with a toothbrush is evergreen, as are the tales about her tying herself to a tree to practice her conducting technique, bricking politicians’ windows while clad in her tweeds, and taking her giant, noisy dog Marco to rehearsals. In many ways this is great — humour was a huge part of Smyth’s character and it would be a shame to downplay that. Being bold and fearless and larger-than-life was what made Smyth who she was. That should be celebrated. The anecdotes are also very memorable, which is so important when introducing lesser-known composers. And purely practically, it’s always good if you can send audiences/listeners/viewers away having had a great time, lots of laughs, and keen to return for more.

The funny anecdotes, though, are only one part of who Smyth was. I’ve spoken in Quartet about the danger of them being used as a way to belittle or sideline her, particularly when they’re heard out of the context of her music, or not balanced by her more serious endeavours. I’m conscious of the fact that I’m rarely prompted to tell funny stories about Sibelius or Shostakovich or Rachmaninov. When I’m invited to speak or write about these individuals, it’s ok to be serious. People want to know about their political opinions and the ways that their music holds up a mirror to their times. It’s taken for granted that they engaged with the politics and philosophy of their day, that they reflected critically on their own experiences, and that their artistic responses to their circumstances have profound wisdoms to impart. Well, women did all of this too. Smyth took her composition just as seriously as any of her contemporaries. And given the opportunity, perhaps some people might find in her music the kind of solace, reflection, and inspiration that others find in Beethoven.

Of course, there’s an extremely obvious and important way in which Beethoven’s and Smyth’s music is different. As was pointed out in the Proms commentary, part of the reason that Beethoven is played so often now is because he’s been played so often in the past. The Ninth Symphony has accrued significance, meaning, and familiarity because of the sheer number of times it has been played in so many different places and contexts. Smyth’s music has had nowhere near this kind of exposure. Her most widely performed work was ‘The March of the Women’, and even so it will have had a tiny number of performances compared to Beethoven’s Ninth. But if we use historical influence as a reason to perform works today, what we’re effectively saying is that works by historical women will never be widely performed. This just perpetuates historical injustices done to women composers. Of course Smyth’s music has not had the same opportunities to be as influential as Beethoven’s. But that shouldn’t stop it from being influential in the future. Now Clara Schumann’s music is being more widely performed and her biography becomes better known, she has inspired works by composers including Gabriela Ortiz and Chloe Knibbs, and been the subject of both fiction and film. Who knows how influential Clara Schumann will become over the next two hundred years?

How we talk about women composers matters. The stories we tell, and who we tell them about, are important. Neither Smyth nor Beethoven were perfect people, far from it. They made mistakes and did dislikable things. But their fallibility is partly what makes them interesting and human. They are imperfect enough to be relatable, and unusual enough to be admirable. If Beethoven has the capacity to be an iconic musical rebel, then so too does Ethel Smyth — tweeds, toothbrush and all.

In other news…

If you’d like to hear more about Smyth and her music then please come along to one of my summer talks about Quartet, including in Edinburgh and Devon! I’ll also be introducing music from Quartet played by Fenella Humphreys and Nicola Eimer at both Snape Maltings and the Barbican. Dates and tickets are available via my website. Quartet is also available to buy in hardback, as an audiobook or as an ebook here.

This is at once brave, moving and insightfully true. Strangely hearing impairments have been much in our discussions recently, as has why we're supposed to always imagine women just weren't (aren't?) as good...

Thanks - cheered up my fundraising night!