It was an unusually mild January, but the crowds hustling in to Plymouth’s Guildhall were still bedecked in jewels, furs, and evening suits to protect against the evening chill. And the crowds were considerable. The evening’s concert was set to be one of the highlights of the 1921 calendar. The music was by the late Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, one of Britain’s best-known composers. Any performance of his music was guaranteed a substantial audience. And it was the first time Plymouth would hear both the famed tenor Roland Hayes, recently arrived from America — and the young woman who now stepped out on the stage in an elegant white dress. Her appearance had been widely publicised, and Plymouth waited with bated breath as the young celebrity took to the platform. Standing beneath the enormous stained glass windows and heavy chandeliers she looked even younger than her seventeen years. And from her first words the audience were spellbound. They recalled her multiple times, and when she finally left the stage after several encores she carried with her a sumptuous floral bouquet, surrounded by waves of applause.

This woman was Avril Coleridge-Taylor — or, as she was then known, Gwendolen Coleridge-Taylor. If she is known at all now, it is perhaps as the daughter of composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, or perhaps as the composer and conductor she became in her later years. But Gwendolen had a multi-faceted career. When she started out, she was famous as a soprano singer, pianist, composer, and as an elocutionist — somebody who gave dramatic recitations, often to musical accompaniment. So who was this woman, who by her teens was so famous that an appearance in Coventry, according to The Midlands Daily Telegraph, ‘created no small stir in local musical circles’, leaving ‘the seating capacity…tested to the utmost’?

In Samuel’s Shadow

Gwendolen was born on 8 March 1903 to the composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor and his wife Jessie, and this family background is crucial for understanding how she made headlines so quickly. Because by the time Gwendolen began performing, Samuel and his music were famous. When one paper described some of his pieces as being ‘too well known to require description’, they were not exaggerating — and this in a period before radio. By the 1920s he was recognised as one of the most exceptional composers of the early twentieth century, and his magnum opus The Song of Hiawatha, an enormous choral work, was routinely performed at venues like the Royal Albert Hall. (Not that it made Samuel any money — he sold the rights to Novello outright, so he and his family did not profit from Hiawatha’s success.)

So from Gwendolen’s very earliest appearances, she was always introduced as her father’s daughter, and she performed her father’s work. In what might be her first public outing as a soloist, when she was thirteen, the papers described how ‘the little daughter of the composer’ sang and danced two of his songs, ‘Big Lady Moon’ and ‘Alone with Mother’. Gwendolen doted on her father, and later championed his work tirelessly, but even so it’s not clear that she would have chosen this career for herself so early in life. Being naturally quite reserved, unlike other child stars like Ruth Gipps, Gwendolen didn’t relish performing. According to Gwendolen’s autobiography, it was her mother who wanted her to sing. Gwendolen had a decidedly difficult relationship with Jessie, which became even more fraught when Samuel died in 1912. Gwendolen lamented that she probably wouldn’t have ‘wanted to do this kind of thing professionally from choice, but my mother saw a way of making money so that I could earn a good deal of my keep.’ And so she found herself on the stage, exhibited as much as exhibiting.

The Coleridge-Taylor factor was amplified by the fact that initially, Gwendolen sometimes performed with her older brother, Hiawatha (named after his father’s work). He had ambitions as a conductor, and as Gwendolen put it, ‘the triple interest was bound to attract. Enthusiastic promoters were not slow to realise that here was a novelty worth exploiting.’ Particularly after World War I, when Hiawatha had been away serving as an ambulance driver, the two were booked as a double act — he on the podium, she on the stage. At the first major Samuel Coleridge-Taylor concert in Ireland, Hiawatha was booked as a conductor, and Gwendolen as both pianist and elocutionist.

Dramatic recitals were a staple of Victorian entertainments, but they have all but died out as a performance tradition. Perhaps thankfully — recitations sometimes involved one person reading the entirety of a Shakespeare play by themselves, which could take several hours. The Daily Telegraph reported that at a reading of Macbeth, after Act II one poor elocutionist’s audience ‘found the attractions of tea greater than those of Shakespeare, with the result that she had to read the remainder of the play to a rapidly dwindling audience.’

Gwendolen’s recitations, however, seem to have been much better received. For a start, she chose more engaging material. Her elocutionary calling-card was The Clown and Columbine, which involved reciting one of Hans Christian Andersen’s melancholy fairy tales with musical accompaniment composed by Samuel Coleridge-Taylor. She performed this across the UK, and her reviews were routinely excellent. When she recited in Wales in 1919, the press reported that ‘the audience were enraptured, and showed their appreciation in a most enthusiastic manner’, and in London the critics noted approvingly that she ‘possesses a keen sense of the dramatic, and we confidently expect to see more of this talented young artiste in the future.’

Finding Gwendolen’s Voice: Gwendolen as Composer

Being the daughter of a famous composer certainly accelerated Gwendolen’s entry into the musical world, but it also put a huge amount of pressure on her shoulders. From the start, all her efforts as a composer fell in her father’s shadow. Her first published song, Good-Bye Butterfly, was deemed evidence that ‘Miss Coleridge-Taylor has inherited a power of musical expression from which much may be expected’. As her composition progressed, she was judged to have either ‘inherited the genius which made her father famous throughout the world’, or, worse, written music in which ‘genius was not perceived’. She was always judged in relation to her father, to the extent that his pieces were sometimes mistaken for hers. The impact this had on her shone through in an interview she gave for The Daily Sketch in 1919:

People are always saying to me, ‘I suppose your aim in life is to be a composer like your father?’ In one way, yes; but it is hard for me to have my compositions compared with those of father’s. People seem to forget that I’m only sixteen and still have time to learn, and I have had no composition lessons yet.

Gwendolen’s early compositions were clearly influenced by Samuel in some ways. But she also has a distinct voice quite her own. She saw herself as a composer first and foremost, and later said that:

Early in life I began to feel a sense of music within me that was anxious to make its way out. Not only did I want to write music — as I had seen my father do — but to express myself through beautiful sound. So, before I was twelve, when most other children amused themselves by playing games, I was concentrating on composition.

Reviews of her compositions were uniformly excellent. She started out writing songs, then moved to piano pieces and works for flute. All of them show a real talent for melody, and her harmonies are inventive. Her music is dramatic in the best sense; her instrumental pieces sometimes feel as though there is a hidden narrative or programme, with the harmony providing unexpected plot twists and turns. Many of her early pieces were published, but perhaps one of the reasons they are so little-known now is because they are tuneful, engaging “character pieces”. There was a real vogue for these in the early twentieth century, and very often composer’s most popular pieces in their lifetimes were these smaller works, like Dorothy Howell’s Humoresque for piano. But they fell out of fashion in the later half of the twentieth century, deprioritised in favour of larger, more “serious” works.

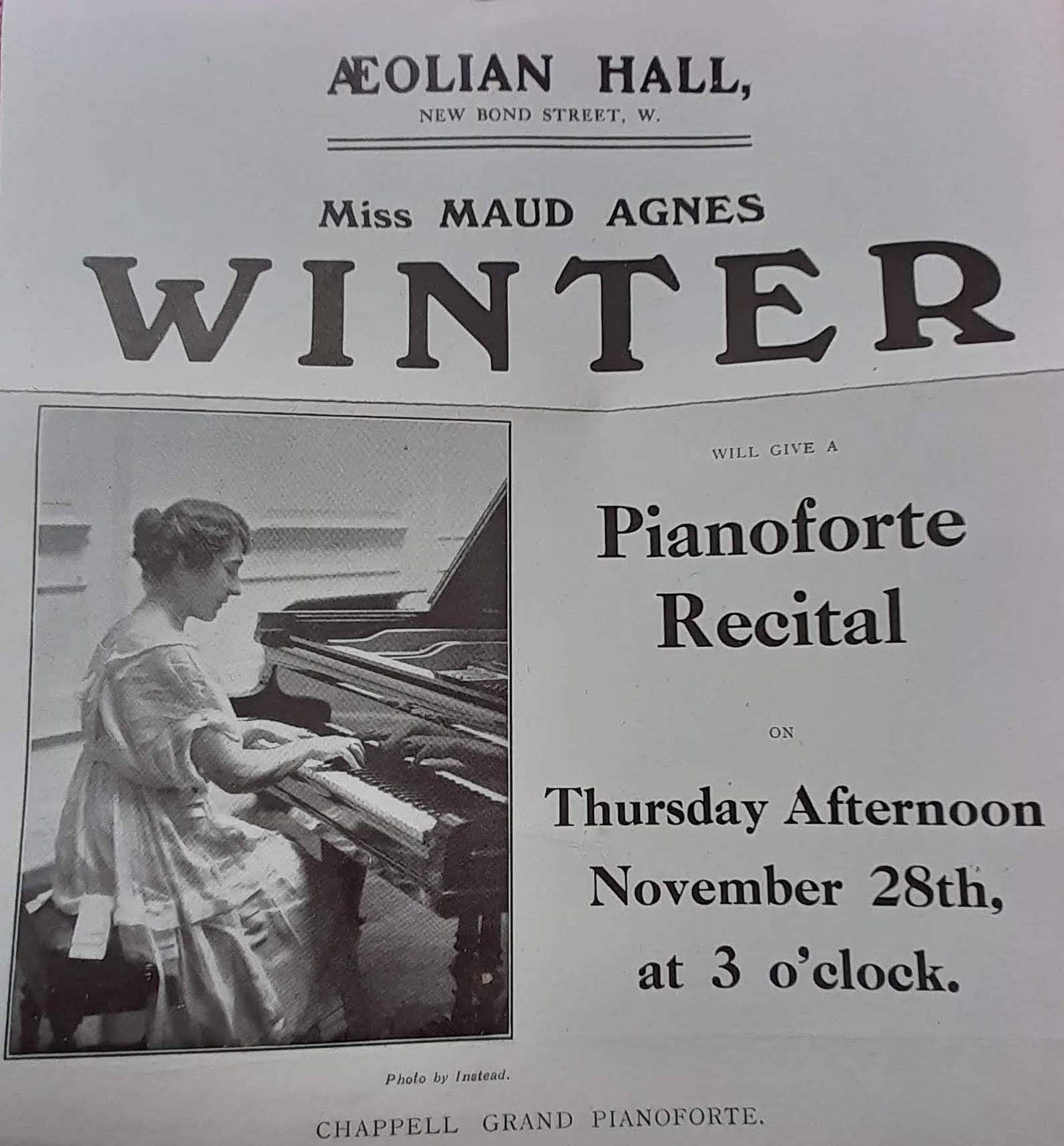

It’s only now that these pieces are starting to get recorded and performed again. I hope that Gwendolen’s music will be treated to a stellar recording soon, because these are really beautiful works. And beyond that, they’re a fascinating window into not only her life, but the lives of many musicians in early twentieth-century England. Gwendolen often wrote music for her social circle, and so through her music we can trace her connections and influences, building a picture of her world. Her piano Interlude, for example, was hailed as ‘a composition of much brilliance’ by The Queen and ‘a brilliant little affair worthy of the attention of the few pianist who can bring themselves to avoid the beaten track’ by The Daily Telegraph. It was written for and premiered by Maud Agnes Winter, Gwendolen’s piano teacher at Trinity College of Music. Little is known about Winter now, but she was one of the many pianists on London’s early twentieth-century circuit who made a career through teaching and the performance of these now-forgotten character pieces.

Gwendolen’s early flute pieces Idylle and Élegie, meanwhile, were composed for the flautist Joseph Slater. They premiered these pieces together, and they performed as a duo throughout the early 1920s. Their collaboration eventually blossomed into an ill-fated romance — but that’s a story for another blog post. For now, her collaboration with Joseph is a piece in the puzzle of how this singer and pianist ultimately became an excellent composer and arranger of orchestral music. Through her collaboration with Joseph, she later recalled, ‘my knowledge of the flute became considerable’. The flute parts of both pieces that she wrote for him are well-crafted and idiomatic, giving the flautist the opportunity to show off to the best of their ability. Both are also passionate and whimsical — it’s tempting to read echoes of her feelings for Joseph into these works. And as for Joseph himself, once his collaboration with Gwendolen ended he went on to be part of the chamber group the Aeolian Players, playing with none other than celebrated violist Rebecca Clarke. As one of the more unusual instrument combinations around (the other members were Constance Izard on violin and Gordon Bryan on piano), the Aeolian were beneficiaries of early broadcasting, regularly booked to break up the schedule of pianists and singers.

Gwendolen managed to get a number of her early works published, but a substantial quantity remained in manuscript, and now reside in a combination of family homes and the Royal College of Music archive. Her Réverie for cello and piano, for instance, was dedicated to and premiered by the cellist Roy Peverett. The reviewers at the time loved this piece, applauding it as having ‘a delightfully fresh and rare quality…intriguing with its bewitching sentiment.’ She also wrote accompaniments for recitations, which she performed herself on numerous occasions and were popular encores. One example is The Elfin Artist, an accompaniment for a poem by Alfred Noyes, which she co-composed with Joseph — perhaps the only instance of her collaboratively composing a work. This, too, was enjoyed by critics, one newspaper calling it ‘wholly delightful’. But these seem to have survived on stages only for as long as Roy, Gwendolen, and Joseph performed them, and they are yet to receive a revival.

Even more of Gwendolen’s unpublished manuscripts have yet to turn up at all. One such loss is her song Whene’er the Sun Goes West, setting a text by Hiawatha. She mentioned this piece in a 1920 interview as a ‘joint effort…undertaken in memory of their father’, but there doesn’t seem to be any other trace of it. Similarly, only one of her three recitation accompaniments collectively called Child Songs, has been found, and her first cello piece Memories, which she described in 1919 as ‘the best I’ve written so far’, has also vanished. (If anybody knows where these pieces are, please contact me!)

Together, though, these published, unpublished, and lost works give a clear impression of Gwendolen as a composer. Right from her very earliest pieces, her compositional voice has a feeling of romance, passion, and idealism. She’s unafraid to take unexpected harmonic paths — and she’s also willing to wallow in rich, lush chords that really eke out every ounce of possible emotion. She needs an interpreter who’s willing to meet her on her own terms. There are moments in her music that could sound schmaltzy or just downright weird in an unsympathetic rendering, but in the right hands can be wistful and truly heart-rending. Hers is a voice that demands — and deserves — to be heard.

You can find out more about Gwendolen’s later life as Avril Coleridge-Taylor in my Radio 3 Sunday Feature, ‘Hidden Women and Silenced Scores’, which also features composers Dorothy Howell and Doreen Carwithen. You can listen on BBC Sounds here.

And if elocution has piqued your interest, Marian Wilson Kimber has a wonderful book about women elocutionists in America, available from Illinois University Press.

I knew nothing of this lady till reading this excellent piece. The quotatons from her regrading herself and her work are instructive. Reading the descriptions of some of her compositions I am reminded a bit of the 'salon music' of Cécile Chaminade, but I could be way off beam here. I shall find out over the months and years.

This is fascinating - a wonderful portrait of her younger days - the sense of her busily creating, rehearsing and performance a huge variety of things... finding her way on stage, despite it not being her passion, and then her voice as a composer... I am looking forward to singing more of her work