Why toilets were a feminist issue

It’s the Jubilee weekend, so I had to write about thrones of some kind.

In the hustle and bustle of Cairo’s Railway Station in December 1913, passing travellers might have been more than a little bemused to find an eccentrically dressed woman preparing to do her business on the floor of the ladies waiting room. They might have been even more confused had they known that this was the famous composer Ethel Smyth, newly arrived from England. She had a reputation for being forthright and outspoken, true, but soiling train platforms was a little outlandish, even for her. Had she finally lost the plot?

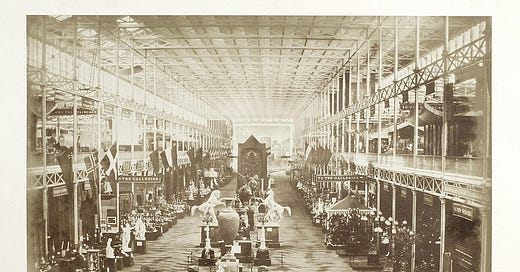

Well, not completely. Because in 1913, the (non)existence of women’s toilets was a feminist issue. Smyth was travelling from London, where for decades the majority of public toilets had been built exclusively for men. Flushing public loos were introduced to the city as early as 1851, constructed for the Great Exhibition, but these proved remarkably divisive. 28 women bought tickets to use the Great Exhibition toilets — compared with 827,252 tickets sold to men. This enormous difference exposes a great deal about Victorian ideas surrounding women’s bodies and morality. Many thought women’s loos were indecent — the slightest hint of a commode raised the thought of women lifting their skirts and exposing themselves, which was far too steamy to be appropriate on London streets. Plus, all those bodily functions were messy and embarrassing. Surely, no respectable lady would be seen entering a public toilet.

The result of this toilet terror was that public spaces were impractical and inhospitable for women. Imagine trying to go shopping, stay out for lunch, go for a long walk — or worse, work — in a city where there were no toilet facilities available. Women could only go as far from home as their bladder could allow. Which was one of the many reasons that department stores like Selfridges were revolutionary spaces — at least for the middle classes. Realising that women could spend more time and money if they didn’t have to leave to pee, department stores provided facilities that gave women a safe space in the city, allowing them to stay away from home for the whole day.

And on this particular issue, London was lagging behind. By 1879, cities like Glasgow and Paris had public toilets for women. But England’s capital, which had nearly 150,000 women employed in trade, didn’t get its first public women’s loos until 1893. Despite sustained campaigning by women’s organisations such as the Ladies Sanitary Association, Londoners were still complaining about public toilets in 1900 — when one was planned for erection on the intersection between Park Street and Camden High Street, cab drivers were allegedly paid to drive in to the makeshift toilet on the proposed site to prove that it would be a public hazard!

Even author George Bernard Shaw weighed in on London’s toilet trouble. He wrote that ‘the exclusion of women from public life is not only an injustice…but an abomination’, and that denying women toilets forced them in to a life of ‘unmentionable suffering and subterfuge’ as they had to rely on ‘little byways and nooks in the borough which afforded any sort of momentary privacy’ to relieve themselves. And it was working class women who suffered most. By 1909, when Shaw penned his essay, most middle-class women could access a bathroom in a department store or women’s club. But having to pay for items in order to use the loos put them out of reach of working class women. Even the few existing public women’s facilities charged a penny to spend a penny — an amount which, as Shaw pointed out, was ‘absolutely prohibitive…for a poor woman.’

Suffragettes were acutely aware of the need for women’s facilities. They were an absolute necessity for women to meet en masse, and to stay on the streets for lengthy periods of time. And this was the context in which Ethel Smyth arrived at Cairo Railway Station, looking for a women’s bathroom. She was a member of the militant Women’s Social and Political Union, had composed their anthem, and was a close friend to Emmeline Pankhurst. Indeed it was to Pankhurst that Smyth wrote home about her excremental exploits. Because when the composer arrived in Cairo and couldn’t find a woman’s toilet, she saw it as part of a pattern of misogyny that tried to keep women out of public spaces and places. Relieving herself on the floor was, therefore, a militant act in support of women’s rights.

Or at least, it would have been, if there really were no women’s toilets at the station. But Smyth had just missed the sign. Oops.

If you want to know more about historical toilets, try Bathroom by Barbara Penner.

Oops indeed! Even in 21st century America public toilets are not easy to find -- public libraries, train and bus stations, stores and restaurants, rest stops on highways, yes. But what to do on a Sunday or holiday when many are closed? There are very few purpose-built public toilets to be found across this nation, at least not in my experience. Some businesses will not allow an individual to use a toilet -- management dictate. I've always been impressed by the abundance of public facilities in Britain, even in the smallest communities on islands. Many have been quite impressive in their design and cleanliness. My rural mountain town in Appalachia is an exception.

A delightful commentary on a topic that few people think about. Well done!

To paraphrase Henry Higgins, "There even are places where public toilets (for both sexes) completely disappear. Well, in America, we haven't used them for years."