It’s a quiet, foggy day when I get out of the car at Berg. Everything is green and still; it takes some time for the mist to lift, and it won’t be until the next morning that I can finally see that the shrouded shapes on the horizon are mountains, the summit of Säntis slowly unfolded by the morning sun. It’s not often that my research takes me to Switzerland, but this week I’m on the trail of a British composer called Freda Swain, whose music — despite her own preoccupation with a very English idea of landscape — has ended up in this Swiss village.

Very little is known about Swain beyond the bare bones of her biography. Born in Portsmouth in 1902, she studied piano at the Tobias Matthay School and was later taught composition by Charles Villiers Stanford at the Royal College of Music. She went on to marry her RCM piano teacher, Arthur Alexander, and the couple lived in Oxford until their deaths; Arthur in 1969, Freda in 1985. When I began researching her a few years ago, her Wikipedia page offered a few tantalising snippets, suggesting that she was a prolific composer. But what that music might sound like was a mystery. Very little of her music was published during her lifetime, and the whereabouts of her manuscripts was unclear.

After doing some digging, I was put in contact with a pianist called Timon Altwegg who was in the process of recording Freda’s piano works. It turned out that although he had never met Freda, through a series of coincidences he had found himself in possession of not just all her manuscripts, but all her papers — poems, letters, the lot. We agreed that I should come to his house to catalogue the material — and after a couple years’ delay because of lockdowns, I’m now here on the German edge of Switzerland to find out who this woman was.

Freda’s belongings came to Timon via one of her own students, who had made some attempt to put some of the papers in order. Apart from that, and Timon organising the major piano and chamber works to digitise and play himself, it’s pretty much as she left it in 1985. So all the material is in plastic boxes, arranged with varying levels of precision. Once the boxes are open, the initial impression is of mayhem — title sheets accompany the wrong pieces, many are missing first or final pages, one box is almost completely stuffed full with pages of sketches unassigned to a completed work. But this isn’t so unusual when it comes to forgotten composers. Much of my early research starts out with turning up on somebody’s doorstep with some cake, then spending weeks in their attic/basement as I work through the papers they inherited when their aunt, grandmother or close friend died. Cataloguing Avril Coleridge-Taylor’s work meant working through plastic boxes full of scores, photographs, letters, cards kept in a bedroom cupboard; Ruth Gipps’s entire oeuvre resides in a garden shed; everything Dorothy Howell left behind when she died (including her recipe books) is kept in apple crates and 1970s chocolate boxes in her niece and nephew’s home.

Visiting these houses really brings home how capricious it can be what goes down as history, and what gets lost completely. Much of this music was not published — if something happens to these papers, that’s it. There are no backup copies carefully preserved in libraries and archives. Tatty, battered and often sellotaped together, these women’s works could so easily have been destroyed or binned. That they have survived so far is purely down to the generosity and care of friends and family members. Or, in this case, the care of somebody who inherited a life’s work entirely by chance.

We make mugs of tea, settle in to the music room where the boxes are kept, and open the first box. It doesn’t take long for it to become clear that even among the usual disarray that I’ve come to expect, Freda’s method of keeping her compositions was particularly chaotic. The dates she gives on her own work list are often incorrect, not matching up with the dates on scores when we find them, and entire pieces are missing. It is half-remembered, unmethodical, haphazard. Timon’s music room is cavernous, but we’ve soon got unidentified pages spread out all over the floor, hoping that we’ll be able to match them up with works over the next few days.

Amid the carnage, though, as we work through the boxes a sense of her personality and who she was starts to emerge. Evidently she had a silly sense of humour that found its way into her music — some pieces have titles like ‘Sorry, Mr Bartók!’ and Quiddities, and a piano Toccata has a note explaining its subtitle, ‘Fakealorum’:

I just heard that delightful word “fakealorum” in the company of Frank Warbrick of Sydney, whereupon it conjured up such an impression of engaging quackery combined with vitality and humour that I felt obliged to try to render it in terms of music.

She taught piano herself, and clearly wrote teaching pieces for her students. I particularly enjoy digging up a set of three short vignettes for voice and piano, ‘Tiger!’ ‘Grasshopper’ and ‘Spiders’, which give a glimpse into Freda’s life as a teacher. They are intended to teach rhythm in a fun and unintimidating way, and were written specifically for one student — the scores indicate that they were penned for ‘Jamie and Miss Swain’.

Yet for all the musical jokes and the seeming carelessness with which her scores were kept, Freda took her music seriously. There are major works here. Gargantuan piano sonatas, a piano concerto, a concert work for violin and orchestra, and string quartets are mixed up with her teaching pieces and unfinished sketches. I run through some pieces on the piano to get a feel for how she writes. Although some of these pieces were performed in Freda’s lifetime and Timon has been recording the solo piano works, it’s likely that for some pieces I am giving world premiere performances right here, to an audience of one — or just to myself when Timon is upstairs making the next round of tea. Freda’s sound combines lyricism with a real grittiness; at first her style reminds me of Ruth Gipps, but Freda’s larger works have far more anger and ferocity than the music of her younger contemporary. There is passion here, and frustration. As I play I can’t help but feel a sense of sadness that such a talented life can end up in this kind of disorder, the music lying unheard for decades.

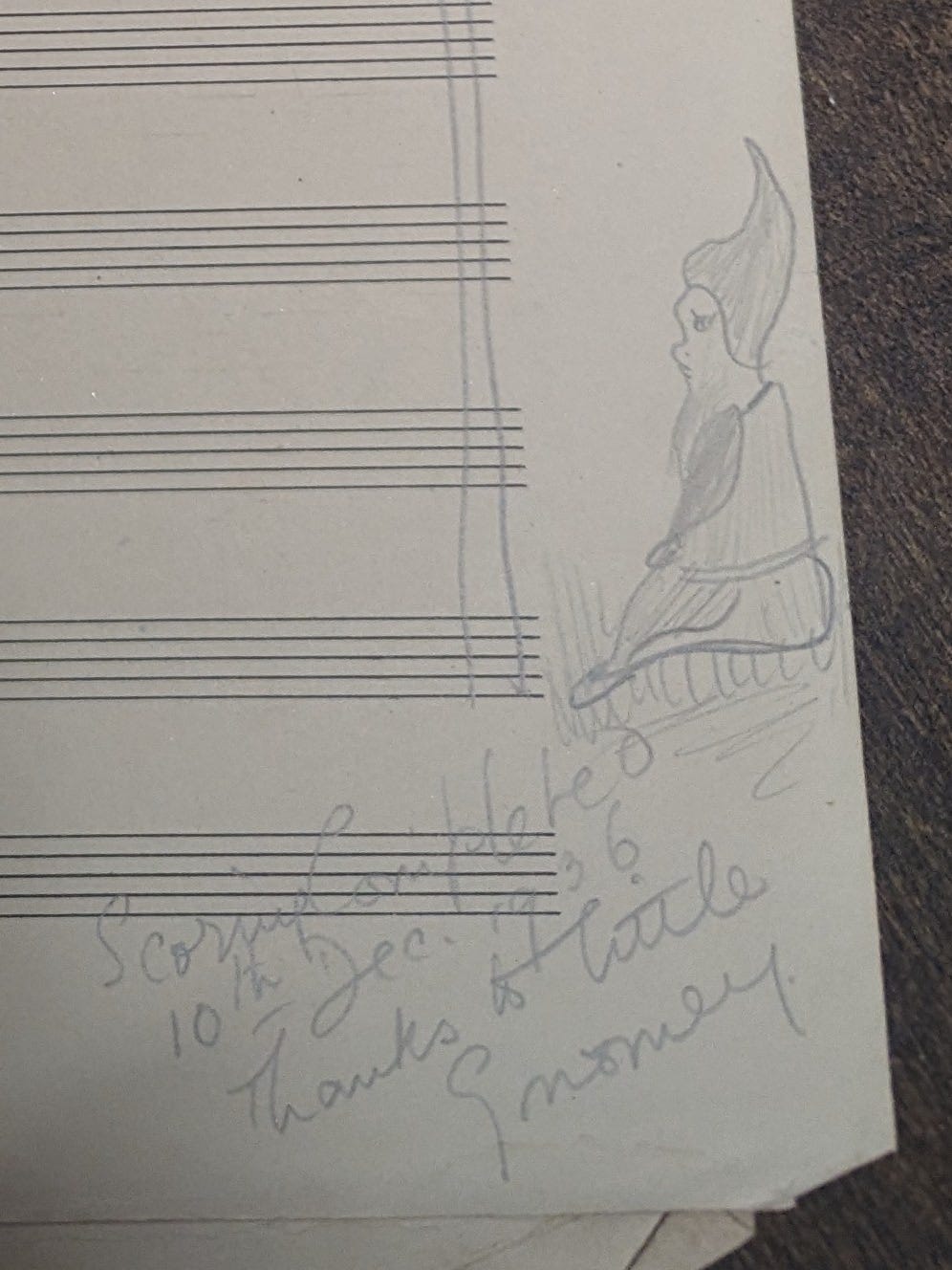

But I feel gladness, too, that somehow this material survives and, thanks to Timon, has been cared for. All her notes are here, her poems, all the little moments that make up a person’s existence. At the end of one work, there’s a note saying ‘Scoring completed 10th Dec. 1936 thanks to little Gnomey’, complete with a small sketch of a garden gnome. Did Freda own a particularly favoured garden gnome? Was this a nickname for somebody else? It feels like she’s reaching out across eighty-seven years to set me a puzzle in her own distinctive brand of humour.

We may not be able to change the neglect of Freda’s music in the past, but thanks to these scores being kept we do have the power to change her future. We work together at the piano, piecing together works that are held together with sellotape. There are moments of real revelation — one piece doesn’t initially make any sense, but once we’ve lined up all the sellotape marks to put it back in order and played it through, what seemed to be scraps turns out to be a complete two piano work. Putting together her entire catalogue will be a lengthy labour of love.

Over the coming months I’ll be working through all of Freda’s music, and will eventually put together a catalogue as I did for Avril Coleridge-Taylor so people can access her work. If you’re interested in performing her music, please contact me and I will put you in touch with Timon. If anybody has information about Freda that they would like to share, please get in contact!

I have just ben clearing a whole lot of "stuff" from my mother's and discovered a folder of letters (and some music) from Freda to my father.

I am about to deposit lots of items from my father's collection to the National Library of Wales Including the Freda Swain file. I thought I would get in touch with you first to see if you were interested!

Philip Lloyd-Eans

Hi Leah,

Thanks for writing such a wonderful article. Freda was one of my great aunts but I never got to meet her (I was just too young but my older sister did). My dad (Christopher Swain, one of her nephews) would love to find out more about her music and get a copy of any manuscripts Timon has, if possible. Piano playing and music in general was very popular on his side of the family and it will mean a lot to him to (and to me) to find out more about her music. Any help would be really appreciated. Best wishes and keep up the great investigative work. :-) Steve Swain